When the landmark Paris Agreement was adopted at COP21 in 2015, nearly 200 nations agreed to keep global temperature rise “well below 2°C” and strive for a 1.5°C target. Now, ten years on, many of those same countries—including some of the world’s biggest emitters—have failed to meet the latest deadline to submit updated climate targets for 2035. Meanwhile, the U.S. has moved to withdraw from the agreement (again), throwing into sharp relief a key question: are the world’s climate commitments enough to curb dangerous warming, or are they merely promises on paper?

A new study led by Professor Ivan Savin (ESCP Business School, Madrid Campus) in collaboration with researchers at Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona takes a deep look at what these pledges—formally known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—really entail. Using computational linguistics to analyze more than 300 NDC documents, the team identified 21 distinct thematic clusters within 7 broader themes, including development, mitigation targets, and impacts of climate change, which reveal how countries frame their climate commitments.

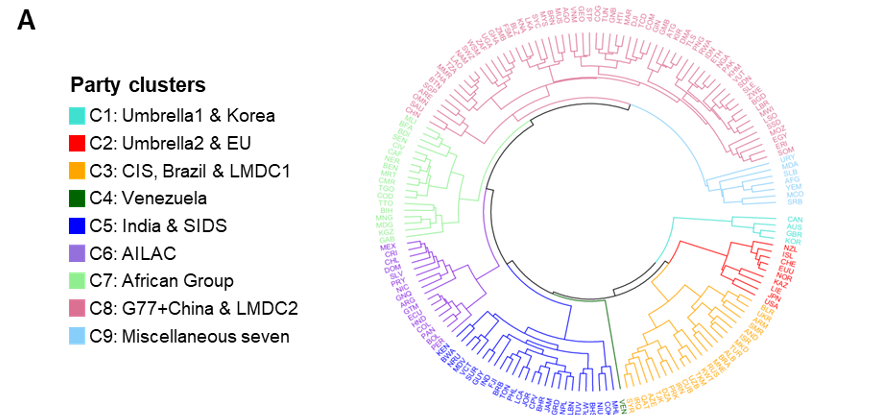

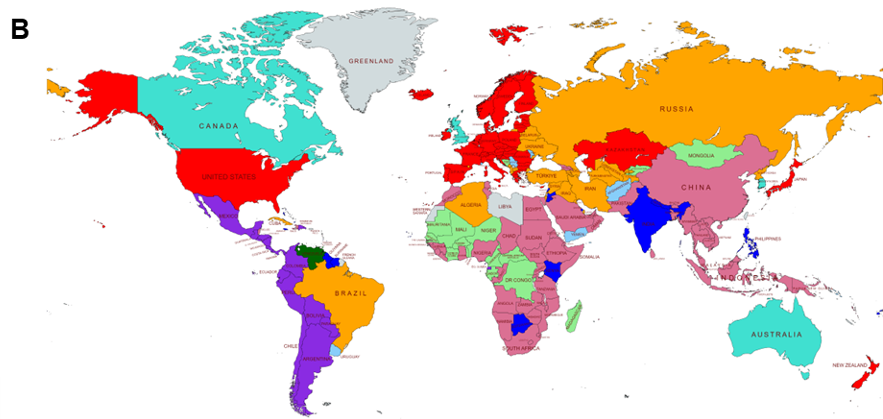

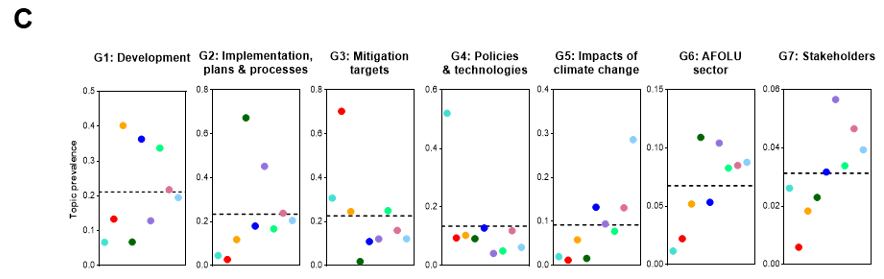

Figure 1. Clusters of parties to the Paris Agreement and topic prevalences

(A) Radial dendrogram clustering parties based on topic prevalences in their NDCs.

(B) Map of nine clusters of parties to the Paris Agreement.

(C) Average prevalence of each of the thematic groups among the identified party clusters.

Note that the y-axes of the seven graphs have different scales. Dashed lines indicate the mean for each thematic group across all nine clusters. Colours are consistent across all three sub-figures.

NDCs: The Backbone of the Paris Agreement

Under the Paris accord, each signatory nation must submit an NDC every five years, laying out specific greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets and strategies to meet them. These can range from sector-specific actions—such as cutting emissions in energy and transportation—to outlining broader financing needs for green projects. Although some countries have complied by the UN’s due dates (most recently February 2025), many have offered minimal updates or missed deadlines entirely, weakening the collective ambition to limit warming to 1.5°C.

What’s an NDC?

- A country’s official roadmap for cutting GHG emissions, spelled out in legislation or strategic plans.

- Required to be updated every five years under the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism,” designed to push ever more ambitious targets.

- Held in a public registry by the UNFCCC, where new and older versions are accessible.

Uneven Details, Uneven Outcomes

Professor Savin’s study exposes significant disparities in how nations present their pledges:

1. Wealthy Nations: Big Targets, Vague on Policy

Countries like the U.S., EU members, and Japan provided quantitative emission-reduction goals but offered limited detail on precisely how they’ll achieve them.

For example:

- The EU’s first NDC was one of the shortest on record—just 1,000 words—with a table of emissions targets but no clear roadmap for implementing policies. Even in its updated submission, details remain vague, with broad statements such as:

“Sustainable transport fuels can play a key role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” - The United States’ updated NDC (2021) sets a 50-52% emissions reduction target below 2005 levels by 2030, but the document’s implementation plan spans only two pages, offering no binding regulatory commitments or financial mechanisms.

Such pledges appear ambitious on paper but lack accountability measures, raising concerns about their effectiveness in achieving real emissions reductions.

2. Developing Economies: Climate Commitments Tied to Economic and Social Justice

By contrast, lower-income countries and climate-vulnerable nations often integrate their climate pledges with broader development goals, emphasizing poverty reduction, social justice, and adaptation finance.

- Many highlight their dependence on financial and technological support from developed nations to implement their climate policies.

- Some, like Ethiopia, provide sector-specific breakdowns of emissions projections and detailed policy interventions—a level of clarity often missing in richer countries’ submissions.

This contrast exposes a deeper climate justice dilemma:

Who should bear the economic burden of climate policies—developed nations with historically high emissions or developing countries striving for economic growth?

This debate reflects the fundamental trade-offs between climate action and economic priorities:

- In wealthier, market-driven economies, policymakers must balance emissions reductions with economic competitiveness—often leading to slow transitions or political pushback from fossil fuel industries.

- In less capitalistic or state-controlled economies, climate policies must consider employment security, energy affordability, and political stability, which may slow down activedecarbonization efforts.

Rather than just scientific or economic disputes, these ideological and political divides shape how nations approach climate action.

Why Standardization Matters

One key takeaway of the study is that NDC formats vary wildly, from under 100 words to tens of thousands. This inconsistency makes it difficult for researchers, policymakers, and the public to track progress or compare across countries. Standardized reporting could vastly improve transparency, forcing governments to articulate how they plan to fund projects and measure results—rather than simply pledging aspirational targets.

“Without clearer, accountable pledges,” Professor Savin warns, “the goals of the Paris Agreement risk remaining only on paper.”

To ensure real progress, COP30 negotiations must push for:

- A common reporting format, with sector-specific emissions targets, timelines, and funding breakdowns.

- Clearer financing commitments, ensuring pledges are backed by realistic budgets.

- Stronger accountability mechanisms, tracking implementation progress through standardized benchmarks.

Such measures would transform NDCs from political statements into actionable blueprints, making it easier for researchers, policymakers, and the public to evaluate progress.

Looking Ahead: COP30 in Brazil

This November, the global spotlight will turn to COP30 in Belém, Brazil—the largest climate conference since the historic Paris summit. With many countries missing their latest deadline to update commitments, the meeting marks a critical juncture: can nations agree on robust, verifiable action that bridges the gap between promises and real-world reductions? Or will political inertia and patchy funding push the world closer to a projected 2.6–2.8°C rise by 2100?

Professor Savin’s research underscores the urgency for:

- Detailed Financing Strategies – Show not just targets, but also how to pay for them.

- Concrete Policy Mechanisms – From phasing out fossil fuel subsidies to adopting carbon pricing, governments must link goals to actions.

- Accountability & Transparency – NDCs should follow a common, comparable format so progress can be measured accurately.

About

Professor Ivan Savin is Associate Professor of Quantitative Analytics at ESCP Business School, Madrid Campus, where he heads the “AI and Robotics” specialization for the Master in Management. His work focuses on environmental economics, climate policy, and the application of complex systems modeling. Before joining ESCP, he was a postdoctoral fellow on ERC-funded climate research at ICTA-UAB and has held positions at Friedrich Schiller University and KIT, exploring how to optimize environmental and innovation policies.

In this study—published in Nature Sustainability—he and his co-authors shed light on the substance behind each country’s climate pledges, demonstrating how textual analytics can uncover hidden priorities, weaknesses, and opportunities. As COP30 nears, their findings stand as a call to leaders, businesses, and civil society: without strong accountability measures, the Paris Agreement risks becoming little more than a decade-old aspiration.

Campuses