The November 25, 2025 meeting of the Reinventing Work Chair was an opportunity to look back on six years of activity and to review the outcomes of the 2023–2025 cycle, while opening perspectives for 2026 on the future of work. Since 2019, the Chair has developed 17 research projects structured around three main pillars: flexibility, practices & roles in hybrid environments, and engagement & leadership. The year 2025 was marked by several key milestones: the redesign of the website, an updated version of the brochure, significant progress on ongoing research projects (onboarding, hybrid management, knowledge management, AI & emotions), as well as the celebration of the Chair’s sixth anniversary — a chance to highlight its contribution to both academic and managerial discussions.

The work presented emphasizes that hybrid work is less an HR policy challenge than a test of managerial maturity. Collective effectiveness depends primarily on the quality of interactions, the clarity of operating rules, and the team’s ability to structure its collaboration. Data shows that a collective presence between 23% and 40% optimizes performance — provided that this presence is intentional, negotiated, and supported by a clear working agreement. This hybrid setup also comes with an intensification of collaborative work: more meetings, more participants, increased time elasticity, and greater fragmentation of information. When combined with the underlying stigma “being present = working,” these trends increase the risk of cognitive overload and make it harder to detect weak signals. They highlight the need to rethink what meaningful presence looks like, as well as the conditions for informal transmission and knowledge sharing.

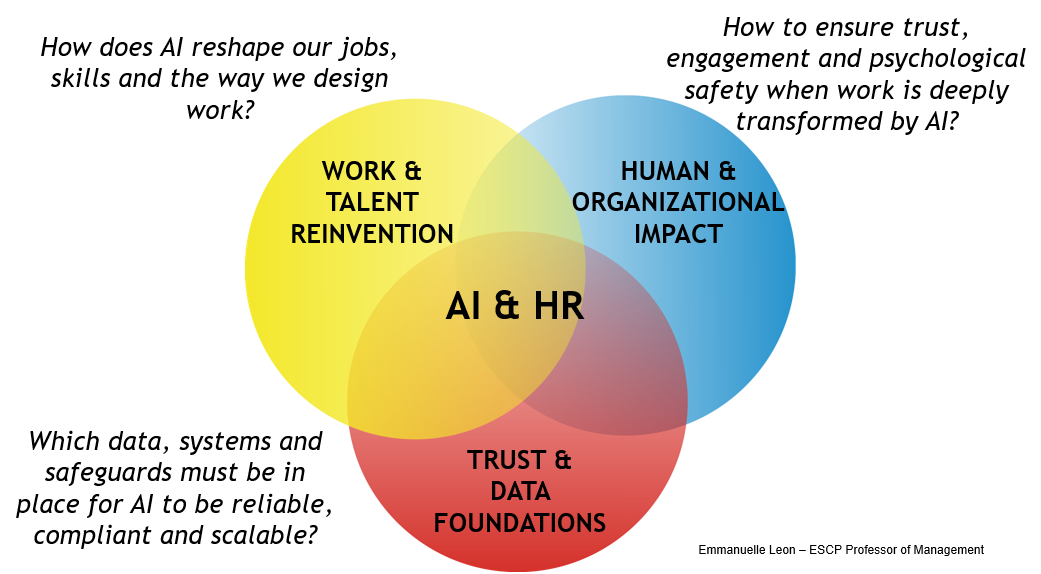

Regarding the impact of AI on work organization, three major transformations are emerging: the automation of an increasing number of tasks, including cognitive ones; the digitalization of tacit knowledge, which shifts the boundary between individual and organizational knowledge; and the rise of algorithmic coordination, which silently reshapes supervision and management practices. The impacts on HR practices need to be considered systemically. AI’s effect on jobs (augmentation, task synergies, or substitution between human and automated tasks) calls for a forward-looking approach to skills. This cannot be done without considering the organization’s culture. Psychological safety is a central element here: can people openly say they did not understand something, express disagreement, or acknowledge a mistake? AI relies on the data it is fed — and what will the quality of that data be if individuals are concerned about the impact of AI on their roles? A systemic, balanced approach — avoiding both technological optimism and pessimism — is therefore essential. Some companies address this by bringing HR and IT functions closer together. This is a promising avenue, provided that both functions truly speak the same language.

While AI is highly effective at improving simple individual tasks (writing, summarizing, email processing), its impact on collective performance remains limited. These technologies are still weakly embedded in complex decision-making processes and critical workflows — even though this is precisely where true organizational value will emerge. The MIT Report 2025 supports this view: despite massive investments, 95% of organizations report no impact on their financial performance. The main barrier lies not in the quality of the models nor in regulation, but in the organization’s learning capacity: contextualizing systems, enriching them through practice, and helping teams build the culture needed for effective human–AI collaboration.

A central topic of the meeting was the differentiated impact of AI depending on the level of expertise. AI significantly narrows the productivity gap between novices and experts, acting as a real accelerator of learning and skills development for junior profiles. For experts, AI can reduce cognitive load and support complex analysis. Yet they are paradoxically the hardest group to engage: they tend to avoid approximations, remain highly vigilant toward errors, value professional judgment, and are sensitive to status considerations. Their buy-in nevertheless conditions the organization’s ability to embed AI into its most critical processes. This tension invites a re-examination of what expertise actually means. Beyond codifiable knowledge, experts play a relational, contextual, and interpretative role: they give meaning, translate, make trade-offs, and ensure coherence between systems and practices. AI does not replace this role; it reshapes it. But a technicist view of expertise — one that reduces it to tasks that can be automated — reinforces substitution fears and weakens engagement.

These issues are closely connected to the questions raised during the meeting, particularly around onboarding and junior training — areas that have become strategic in several regions, such as Singapore. In this regard, the Learning AI by AI project, conducted with Rakoono, explores learning dynamics between experts and AI, focusing on the role of moral emotions — shame, fear, pride — in adopting AI tools. The project examines experts’ ability to see AI as a partner, to expose themselves to its errors or approximations, and to integrate these interactions into a learning trajectory. It also investigates how AI reshapes the meaning of work, engagement, motivation, and, more broadly, the conditions of human–machine collaboration. This work opens a deeper reflection on how expertise boundaries are being redefined and which organizational levers can support responsible and sustainable adoption.

Campuses