Amid mounting warnings over biodiversity loss, a new generation of startups is attempting to reshape how we value and manage Europe’s natural capital. One of those is Maa Biodiversity, a French startup that combines ecological science with hands-on land management and new forms of environmental finance, which is also a part of ESCP’s incubator, Blue Factory.

Founded by three alumni of ESCP – Hippolyte Bruguière, Aristide Bruguière and Younes Boual – Maa is part of a growing movement of “nature tech” companies seeking to give biodiversity the same financial and policy visibility carbon emissions have enjoyed over the past decade.

But where others have focused on recommendations and reporting, Maa’s approach is resolutely field-focused.

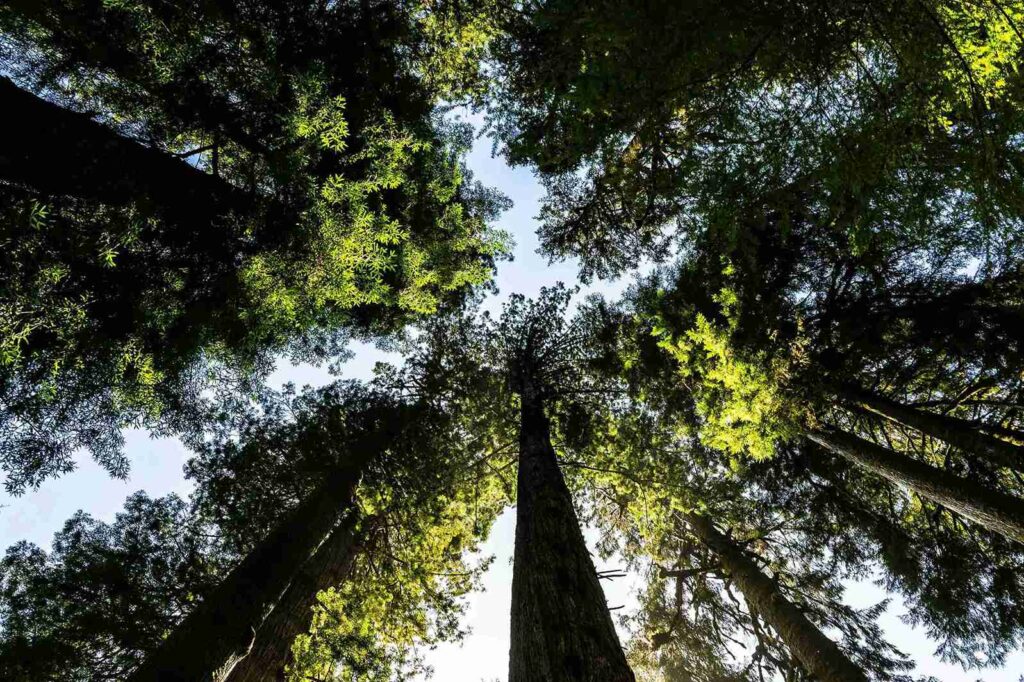

“We protect biodiversity by going into forests,” Aristide Bruguière says, noting that forests are home to about 80% of all land-based species. But according to the UN, biodiversity is disappearing at an unprecedented rate.

Images of deforestation in South America or Southeast Asia tend to grab the headlines. But Bruguière points out that Europe is experiencing a quiet decline in forest health and ecosystem quality, even as total forest area continues to expand.

Europe’s forest area has grown by roughly 9% over the past 30 years, according to Forest Europe. But nearly one in four trees shows signs of defoliation, a marker of systemic stress, the European Environment Agency says.

“The issue is not deforestation; it’s bad reforestation,” Bruguière explains. “You get low biodiversity, fragile forests and a rise in wildfires and disease.”

The problem, in essence, is not the absence of trees — but the absence of life within them.

The issue is not deforestation; it’s bad reforestation. You get low biodiversity, fragile forests and a rise in wildfires and disease.

Turning carbon tools toward biodiversity

Maa’s answer is to rewire the incentives for landowners and corporations alike. The company works with private forest owners, paying them to preserve their land instead of cutting it down. Maa then manages the forest, improves its health and issues carbon credits to fund biodiversity restoration.

“We’re not focused on capturing carbon — forests do that on their own — but we use carbon credits as a way to secure funding for active biodiversity protection,” says Bruguière.

Carbon credits are certificates that represent one tonne of carbon dioxide either avoided or removed from the atmosphere — and can be bought and sold to offset emissions.

Maa is currently working with six forest owners across 2,000 hectares, with plans to scale up to 10,000 hectares by mid-2026. The challenge, however, is not access to land. It is access to capital.

“We pay forest owners annual rent to manage their land,” Bruguière says. “When necessary, we harvest wood sustainably and generate carbon credits from the areas we conserve. That allows us to offer landowners nearly the same income they’d get from cutting down their trees — while protecting biodiversity.”

Listening to the forest

Central to Maa’s proposition is a hybrid methodology developed in collaboration with a French public institution. It combines satellite imagery, soil sampling and sensors that listen to the forest to map the diversity of species. These tools help Maa measure how healthy a forest is, and track changes over time.

“We go directly into the field and use bioacoustic boxes — devices that record all the sounds made by birds and other animals in the forest,” Bruguière explains. “We also take soil samples to analyse which nutrients and ecosystems are present or missing.”

Maa turns this data into a scoring system to track progress and decide what actions are needed. That could mean carefully cutting certain trees, planting species better suited to future climate conditions, or taking steps to reduce the risk of wildfires.

Maa carries out the work directly. “If trees need to be harvested, we hire lumberjacks to handle it,” explains Bruguière. This hands-on model sets it apart from some other players in the biodiversity space, which tend to be limited to audits or advice.

We’re not promising to protect nature in the future — we protect it from the moment we intervene. Our results are based on real data from the field.

Measuring what matters

While many nature-focused projects chase big numbers, Maa focuses on doing the work well and proving it. One of its main goals is to manage 20,000 hectares of forest — land that’s not just protected, but clearly improving over time.

“For us, it’s about protecting biodiversity. The more land we manage, the more we can make sure it’s being done properly,” Bruguière says. “We apply our method three times over the course of each project: to set a baseline, track changes and reduce risks on the site.”

A market in flux

Europe’s market for nature-based solutions is still developing. Regulation is tightening, and voluntary carbon markets are under growing scrutiny. Credit prices have declined, in part due to oversupply from low-quality projects.

“The carbon market is evolving quickly,” says Bruguière. “Prices have dropped mainly because of large projects flooding the market with credits, many of them lacking transparency.”

By contrast, Maa’s results are rooted in observable outcomes, not future projections. This, Bruguière argues, is where market credibility is heading.

“We’re not promising to protect nature in the future — we protect it from the moment we intervene,” he says. “Our results are based on real data from the field.”

A future for functional forests

As Europe looks for ways to use land more sustainably, Maa offers a practical model that connects business, science and nature. It’s not without challenges: the work requires massive funding, depends on changing regulations and faces growing competition from other ESG-focused startups.

But for Bruguière, the logic is simple.

“We’re not treating nature protection as charity,” he says. “We’re building a market-based model that gives landowners and companies a reason to protect biodiversity.”