In the article which won the 2019 Best Paper Award of the IEEE TEMS (Technology & Engineering Management Society), professor Florian Lüdeke-Freund and his co-authors provide a better understanding of the interplay and complementarity of internationally distributed “technology/manufacturing push” and “demand pull” policies within the context of environmental technologies. Their findings could help in the adoption of these technologies, which is important to governments as it is linked to the public good (i.e., climate change mitigation).

The global reduction of greenhouse gases requires the adoption of energy conservation as well as sustainable generation, involving global changes such as virtually eliminating fossil fuels. Because they are linked to the public good, environmental innovations like renewable energy (RE) technologies are thus important to governments. But there are barriers to their development and implementation, and academics have been debating the relative importance and timing of the relative contributions of two types of policies, broadly categorized as “technology push” and “demand pull.” “Particularly, the diffusion of environmental innovations requires a “regulatory push/pull”, with technology push policies aiming at facilitating R&D and related financing, and demand pull policies to increase adoption,” write the head of ESCP Business School’s Chair for Corporate Sustainability and Master in Sustainability Entrepreneurship and Innovation, the head of Johannes Kepler University Linz's Institute for Integrated Quality Design, - Erik. G. Hansen -, Xiaohong Iris Quan (San Jose State University) and Joel West (Keck Graduate Institute) in their paper.

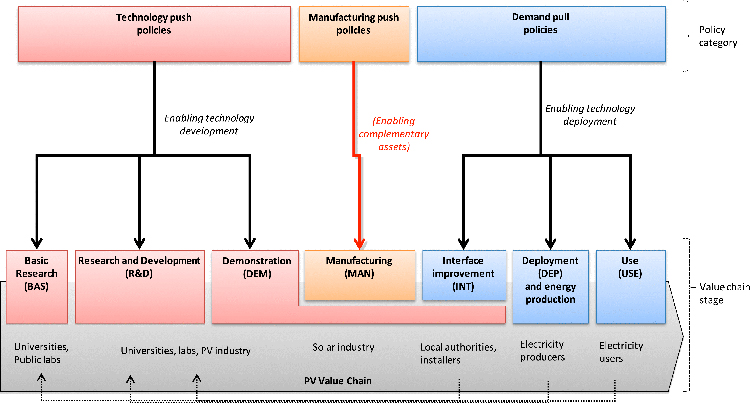

They explain that while technology push and demand pull policy analysis has often emphasized a specific national context, researchers have increasingly acknowledged that technology innovation occurs across national borders or even in a global division of labour. Hence, recent studies look at interactions between different countries and their technology policies but even when they show the effect of domestic RE policies on foreign innovation, they do not analyse interactions between policies of different nations. Other studies provide more fine-grained policy analyses within a broader (technology) innovation systems perspective with a dedicated look at how international policies influence each other. These studies also take into account the specific role of manufacturing in technology adoption, including policies that focus on promoting manufacturing, which the authors term “manufacturing push.”

This is why Lüdeke-Freund and his co-authors carried out a qualitative longitudinal analysis based on secondary data covering 40 years (1974–2013) of policies regarding one RE - solar photovoltaic (PV) - for three major economies – the USA, Germany and China -, which culminated in the publication of their research in a prestigious review as well as a Best Paper Award. “We started our research on solar policies in 2010 and finished the paper in 2017 – it was quite a journey. That the product of our team effort finally made it into a leading engineering journal, and received this award, surprised us all quite a bit,” Lüdeke-Freund explains.

They identified four phases of international policy interactions: in Phase 1 (1974-1990), the USA launched technology push policies; in Phase 2 (1991-2003), Germany pioneered demand pull policies; in Phase 3 (2004-2008), China responded to international market incentive programs with a scaling up of manufacturing; and in Phase 4 (2008-2013), Germany reduced whereas China increased demand policies.

Their contribution to research on environmental technology innovation is threefold:

- Their results extend the technology push/demand pull dichotomy by highlighting the importance of manufacturing push for scaling up manufacturing. Technology push, manufacturing push, and demand pull policies address different parts of the PV value chain.

- They also show how these three policy categories can interact and how complementary international policy specialization and their interdependencies can enable the global diffusion of environmental technology.

- Finally, they consider the trade-offs in climate change policy between global environmental welfare success (adoption of PV or RE, respectively) and national economic failure (if demand incentives in one country create jobs in another).

Campus

![© Pexels - Pixabay [copyright]](/sites/default/files/styles/event_news_une/public/2020-09/Lu%CC%88decke_award1.jpg?itok=nhGsUTFi)